in 2009, two teenagers in the Democratic Republic of Congo showed up at

their village health clinic, vomiting and with blood in their noses and

mouths — hemorrhagic symptoms of the notorious Ebola viruses. In three

days they were dead.

Yet it took three years for researchers to unmask the likely culprit: a brand-new virus called Bas-Congo, which is not related to Ebola or any other virus known to cause severe hemorrhagic fever.

It can take weeks or months to identify a novel virus, and

much longer if the sample must be sent to a specialized lab, as the

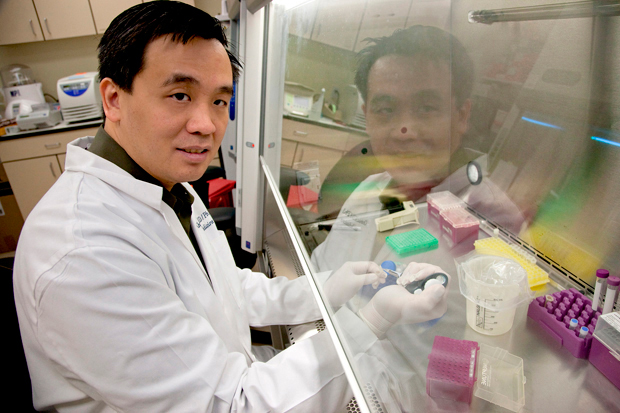

Bas-Congo virus was. Such lags are too long, says virologist Charles

Chiu, director of the Viral Diagnostics and Discovery Center at the

University of California in San Francisco.

Deciphering a virus’s genetic code is the critical first

step in determining how fast it might spread, identifying possible

treatments and even finding vaccines. Viruses like the one that killed

the Congolese teens can quickly go global, and traditional methods for

identifying viruses, which only test for one pathogen at a time, could

mean sacrificing untold lives.

But Chiu and his colleagues have found a way to speed up virus identification — a method

they hope will one day help health care workers in remote areas

identify new viruses as soon as they appear, as long as they are able to

access the Web.

The team conducted a proof-of-concept test in which they eventually identified the Congolese virus.

Typically, it takes three months to piece together a

complete viral genetic code. The new process can identify an unknown

virus in less than two hours, and Chiu’s team can put together the

entire genetic code of a virus in a single day.

Chiu’s colleagues are working to get more DNA sequencers —

and expertise to use them — into the hands of health care workers in

potential virus hotbeds. Meanwhile, Chiu and his team hope to put their

virus-identifying system on the Web so health workers anywhere can

access it.

Chiu’s vision: When patients show up at a clinic with an

unknown pathogen, health care workers could take swabs and run DNA

sequences onsite, then use smartphones or laptops to feed the results to

an online network that would deliver results in minutes.

[This article originally appeared in print as "The Race to Peg a Virus."]

Proof-of-Concept Test

1. Starting with a sample of the Bas-Congo virus, Chiu and colleagues

first grew the virus in culture, then extracted its genetic material

and made millions of copies.

2. Next, they put the samples into an instrument called a DNA

sequencer — which automatically analyzes genetic material — to read

short viral gene fragments millions or even billions of times.

3. Finally, they ran the results through a software program that

combed through many gene sequences simultaneously, comparing each one

with the sequences of known viruses stored in online databases. This

process allowed them to home in on the identity of the virus.